I’ve been a professional environmentalist for over 15 years. People actually pay me to protect the places I love and the most vulnerable communities and species  on the planet. It’s an incredible privilege, and every day I feel gratitude for the faith and support people have given me. Even so, I’ve come to a painful realization: my entire career to date, the careers of all my contemporaries, the career of every environmentalist that came before me—all of our work has been a total failure.

on the planet. It’s an incredible privilege, and every day I feel gratitude for the faith and support people have given me. Even so, I’ve come to a painful realization: my entire career to date, the careers of all my contemporaries, the career of every environmentalist that came before me—all of our work has been a total failure.

Now, you could quibble with that statement. After all, the Clean Air Act has provided the United States with billions of dollars in benefits above and beyond what it’s cost us to clean our air. We’ve protected millions of the most beautiful and biologically rich landscapes as National Parks and Wilderness Areas. Even my own career has been marked with legal and political victories, protecting endangered species and disadvantaged communities from harm. These are all worth celebrating, and they have all been essential to preserving the magic and beauty of this world.

But when it comes to the most challenging, largest-scale environmental problems we face—the amount of carbon in the atmosphere, the numbers of species on the brink of extinction, the degree of inequity across our human communities—things have been getting worse. Even more disconcerting, when we consider the derivative of these trends, on average they are getting worse at increasingly faster rates.

Environmentalists recognize this profoundly. But to carry on we compartmentalize and bury this problem in the recesses of our mind. We do this because hope remains the most pervasive motivation for our work: we act because we are hopeful that somehow our collective, cumulative action will amount to a solution, saving the things we treasure most.

However, in a world where things are trending the wrong way, hope is irrational; and in the absence of some other motivation to do what we do, our hope dissipates, we despair and we quit—which compounds our sense of hopelessness. This is the dilemma of our hope: we understand our movement must change to nurture hope, yet the scale and rate of necessary change is so extraordinary that considering change leads to hopelessness.

In our desperation to escape this dilemma, environmentalism can be co-opted by self-appointed oracles that falsely promise to regenerate hope by cherry-picking data and pretending to score when they’ve only moved the goal post. These post-environmentalists, as we’ve come to call them, can be almost impossible to defrock when they are embedded in trusted institutions, and even more so when they initiate their conversion by acknowledging the failure that we know in our deepest recesses to be true.

Which brings us to Dr. Peter Kareiva, chief scientist for the Nature Conservancy, and his recently-launched blitzkrieg against conservation and the environmental movement as we know it. His attack begins with an observation we have all made at one time or another: at some fundamental level our movement is failing and needs to be re-examined.[1]

From this common ground, however, Kareiva launches into a controversial—and fundamentally baseless—attack on the environmental and conservation movement. Rehashing almost verbatim the arguments made two decades ago by the Wise Use movement—whose purpose, according to Ron Arnold (its most prominent figurehead), was “to destroy environmentalists by taking away their money and their members”[2]—Kareiva urges us to give-up “idealized” and “nostalgic” campaigns for nature, parks, and wilderness, and replace them with campaigns that promote “the right kind” of development, in partnership with “visionary” corporations, so that our purpose becomes to “benefit the widest number of people.”[3]

When the Wise Use movement first made similar arguments, most conservationists and environmentalists challenged their assertions without hesitation. The Wise Use platform made it easy for us to do so: after all, choosing between wildness for all or timber profits for some is not a difficult choice.

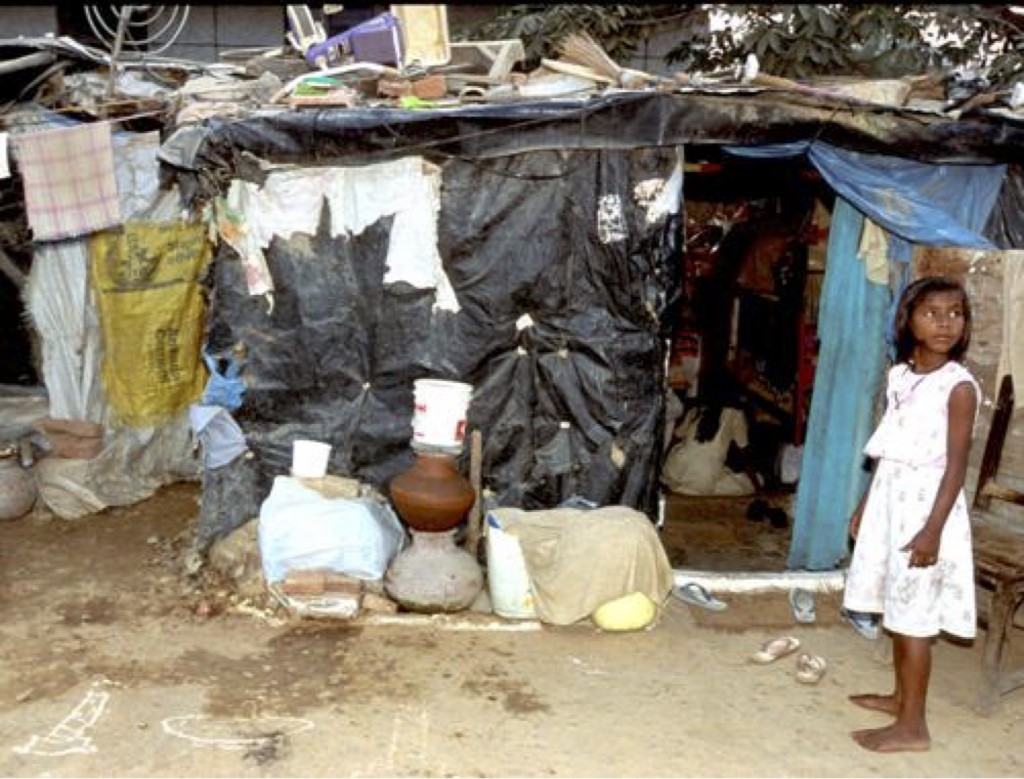

Kareiva wields the same logic, but he has muted our movement’s response by pitting wildness not against some tried and true foe, but against the welfare of the world’s poorest people. Where the Wise Use movement suggested wilderness should be abandoned so we may extract more profit from, and exercise more freedom in, the land, Kareiva suggests wilderness should be abandoned so that the global poor can use the land to rise out of poverty.[4]

This is political expediency at its lowest, most debased form. Rather than confronting power and extracting reparations from the forces behind western colonization, Kareiva proposes to exploit the next most vulnerable community we can find—the nonhuman world. Perhaps this is a natural consequence of the Nature Conservancy’s management team, which includes more representatives of multinational corporations than conservation scientists, making it incapable of holding the world’s economic power structure accountable for its immoral acts.

Yet at the same time, because Kareiva works for the wealthiest and arguably most well-known environmental organization ever to exist, some pundits and foundations, desperate for a shiny new prophet of hope, have jumped on his bandwagon. They are demanding we hold those things that are least like us—the rainforests, the last Bengal tigers, the wilderness near your home—responsible for the unjust acts of western colonial power, and make these lands and species pay the debt that western civilization incurred.

While this may be an effective way to ameliorate the injustices suffered by the global poor from centuries of western colonialism, it simply extends colonial power over the most vulnerable, least powerful creatures on Earth. Kareiva thus leaves us in an equally unsatisfying moral position: if you believe that we have moral obligations to the animals, plants, and ecosystems that accompany us on Earth. But this is where the breech with these post-environmentalists becomes most striking. Kareiva affirmatively states that we must abandon our ethical concerns for other forms of life[5]—not to mention the systems that sustain life altogether—because, in his judgment, such a movement is unscientific and ultimately cannot be successful.[6]

The Ethical Critique

For Kareiva to suggest that the scientific evidence we have collected in our heads is somehow more powerful than the ache that we feel in our hearts, he must ignore the contextual history of ecological wreckage that gave birth to our campaigns for nature, parks, and wildness in the first place. This is a critical oversight, because environmentalism and conservation are an ethical response to the sad history of our modern world: every place western civilization reached, it destroyed.

While it’s true that western civilization has, on occasion, demonstrated some capacity for restraint and humility towards the land, our most profound environmental ethicists as well as our coldest utilitarian conservationists have long recognized that too often we denude the lands in which we live—which is why Leopold advocated for a land ethic and Pinchot for sustained yield. But while Leopold urged us to restrain the rapid and violent change our civilization unleashed on the land, Kareiva urges us to embrace it: because, he suggests, the wilderness protections Leopold and others proposed are too cumbersome to craft landscapes people actually desire.[7]

If you lived when the conservation movement was founded, however, a weighty tool was an obvious necessity, because every civilized or cultivated land you observed was also biologically impoverished. The apparent way to preserve anything in such a context is to block civilization from establishing any foothold, even a pastoral one. Moreover, if you believe, as the founders of our movements did, that this planet has value beyond what we can reshape into our image, designating wilderness is an act of humility: a pronouncement that we will refrain from making every speck of this planet a reflection of ourselves.

The ethical rationale for conservation is not only ignored by Kareiva, it is affirmatively rejected.[8] And yet if anything the division of land between us and the rest of life on Earth has become more inequitable since the conservation movement was founded. Our pervasive influence makes post-environmentalists like Kareiva, who calculate the value of nature in utilitarian terms, confused and uncertain about wildness. After all, if everywhere you look you see a reflection of yourself, the very idea of ‘nature’ or ‘wild’ can seem antiquated.

But for those who see wilderness as a proxy for a more just and sustainable relationship with other forms and systems of life, the growing influence of our species everywhere causes us to defend wildness resolutely anywhere.

Of course, today is not the late 1800s, when preservation first found footing in national policies, or even the 1970s, during the high-water moment of the modern environmental movement, when even Republican President Richard Nixon proclaimed we must enact “reparations”—a quintessential moral act—for the Earth.[9] Perhaps today’s post-environmentalists have discovered how to blaze a new path where our civilization grows while the rest of life on Earth ekes by.

However, if we blaze that path in areas that are set aside as reparations for the inequitable relationship we’ve had with the land, we are not implementing some new conservation paradigm. Because the wild isn’t out-of-whack. It’s a San Francisco Bay Delta that is 1/3 landfill; it’s a California that has destroyed more than 90% of its wetlands; it’s a continent that has destroyed all but 4% of its old growth forests; it’s a civilization that continues to burn carbon even though we have near-complete knowledge that the world’s most impoverished and politically powerless communities—including the world’s plant and animals that are so devoid of our consideration that it is nearly impossible to include them within the phrase ‘powerless community’—will be disproportionately burdened by this insatiable pyromania of the most privileged hominids ever to walk Earth.

The Tactical Critique

Far from making our movement more successful, Kareiva’s post-environmentalism will almost certainly lead to its suicide. This is so because the scale of the threat we face dwarfs the resources we bring to bear against it. Kareiva’s proposal will do the opposite of growing our movement to the appropriate scale: it would triage it, giving up on issues he deems unwinnable.[10] In so doing, we will also lose the allies that made these issues their life’s work: and decrease the probability that we will grow to the scale necessary to save the world, or at least keep it from becoming biologically impoverished.

That Kareiva promotes inherently contradictory tactics shouldn’t be surprising, because he is not a sociologist—indeed, his failure to compare and contrast our movement to any other social movement indicates that he is completely ignorant of this field of work. It’s ironic that Kareiva didn’t stop himself from espousing such empirically unsupported policy prescriptions, because a cornerstone of his critique is that everyday environmental activists make assertions without adequate empirical data to back them up. [11]

But even where Kareiva should be in a favorable position to critique environmentalism—pitting his expertise and experience with the scientific method against mom & pop environmentalists that want nothing more than to preserve the landscapes dear to their hearts—he misses the point entirely. As with many environmental issues, the assertions Kareiva derides are made out of precaution: they suggest that in the absence of statistical certainty that some act of exploitation will be benign, we should protect the world—rather than empower those who wish to use or destroy it. Perhaps you could argue, for example, that it’s bad science when an environmentalist demands labeling of foods containing GMOs, if it is not possible to reject the null hypothesis that GMOs are safe—and technically you’d be right. But the demand for labeling is not based on scientific precision—it is demand out of sense of justice, a sense that our efforts to preserve the world deserve the benefit of the doubt when the data is fuzzy or incomplete. This is not bad science, it is justice: an act that places the evidentiary burden on those who profit from risky behavior, rather than on those that happen to be on the wrong side of a null hypothesis.

Admittedly, even if Kareiva’s post-environmental tactics could end our failures, I would still oppose it—because I do not want to live in a world where we have to destroy nature and wildness in order to have gardens, anymore than I would find it acceptable to live in a world where slavery was condoned for the good of the slaves. I would rather fight against such nonsense and lose than claim that as victory.

This brings me back to the problem created by our sole reliance on hope to engage the world. Remaining hopeful is an essential motivating condition for any social movement. But unless we also wield other motivating forces, when the trends seem insurmountable and our hope wanes we run the risk of quitting the movement altogether. Or if, even in despair, we are too involved to extricate ourselves completely from the struggle, our desperation for some ray of hope makes us susceptible to false prophets like Kareiva and the post-environmentalists of this world.

Thus I no longer believe hope is sufficient to weather the storm. We need to also be in touch with our anger.

There is great prejudice, particularly among progressive movements, against anger—and for good reason: there are too many examples where thoughtless rage, a cousin of anger, has set social movements aback or adrift, and caused untold suffering.

When I refer to anger, however, I mean the stirring you feel in your gut when you see a bully stealing a child’s lunch money. The indignation that rises within you when unjust wars are waged in your name. It’s that fierce green fire that Leopold witnessed, even as he extinguished it from a wolf. Such tempered anger never leads to despair: indeed it is what drives you to fight against injustice even when you know full well that you, and possibly no one, will live long enough to see the injustice resolved.

Kareiva’s proposal eliminates any possibility of utilizing anger to motivate our movement, because it is nothing more than an experiment in political expediency. Expediency is by definition unjust: it is an act or acts that gives advantage to those with more power while making the world less equitable. It is difficult, perhaps impossible, to feel indignation against the unjust distribution of the world between people and all life on Earth when you are purposefully making the distribution even less equitable at the same time.

An Alternative Exists

Yet it is true that our movement faces unprecedented, almost insurmountable challenges, and that we need to find new ways to engage them, or we will continue to fail as we have to date.

Dave Foreman—a co-founder of Earth First! & the Wildlands Project and author of Confessions of an Eco-Warrior—has put forward one alternative in a provocative essay titled “The Myth of the Environmental Movement.” In it he suggests that the conservation movement and the environmental movement are two distinct—and very different—movements.[12]

Dave’s article is on to something—it’s true that our use of the words ”conservation” and ”environment” has become sloppy, and they can often mean conflicting things to different people.

But what creates fissures within the broader conservation/environmental movement isn’t found in their divergent subjects of concern—which Dave suggests is wildlife on the one hand, people on the other—but in their divergent rationales and ethical foundations.

The organization—experiment really—that I founded a few years ago called Wild Equity Institute believes that stopping extinction is a moral imperative-–not because biodiversity is good for people, but because it is wrong to cause the catastrophic extinction of species. And today extinction rates are exceptional—orders of magnitude greater than what life scientists call the “background rate of extinction.” However, for Kareiva and the post-environmentalists, preventing extinction is a utilitarian exercise: they believe it is only wrong to let species go extinct if this or that species may have some human use.[13]

A utilitarian conservationist is likely to conflict with an ethical conservationist in many cases. For example, if a particular species has no demonstrable value to people or the ecosystem services upon which people depend, a utilitarian point of view might suggest we need not be too concerned and can allow the species to go extinct, even as the ethical conservationist would argue the exact opposite point. Yet because the object of concern—the conservation status of other forms of life—is identical for both the ethical and utilitarian person, it seems logical, at first blush, to consider both to be part of the same movement, even though their positions are profoundly different. (Indeed, the Endangered Species Act’s legislative history reflects both moral and utilitarian reasons for conserving wildlife and plants.)

An analogous disjuncture is true for those within the environmental/conservation movement that focus on human well-being. Some people advocate for improved quality of life because they believe it is morally wrong to cause harm to other people by polluting for profit. The environmental justice movement is the most obvious example of this ethical concern, and nearly every other element of the environmental movement instantiates this ethos when trying to protect those without political power (consumers, kids, etc.) from those with it (agribusiness, petrochemical companies, etc.). But there are also people who are involved in human health movements simply because they want to breathe clean air, or drink safe water, or ensure that they have a safe place to recreate. This is a more utilitarian rationale for an environmental concern.

An analogous disjuncture is true for those within the environmental/conservation movement that focus on human well-being. Some people advocate for improved quality of life because they believe it is morally wrong to cause harm to other people by polluting for profit. The environmental justice movement is the most obvious example of this ethical concern, and nearly every other element of the environmental movement instantiates this ethos when trying to protect those without political power (consumers, kids, etc.) from those with it (agribusiness, petrochemical companies, etc.). But there are also people who are involved in human health movements simply because they want to breathe clean air, or drink safe water, or ensure that they have a safe place to recreate. This is a more utilitarian rationale for an environmental concern.

What ultimately creates a fissure in the environmental/conservation movements is not the subjects of our concerns, but the rationales for our concerns in the first place. If you are a conservationist by moral imperative, you will probably have more in common with those who are environmentalists by moral imperative than you will with a utilitarian conservationist. Similarly, the utilitarian conservationist and the utilitarian environmentalist are likely to have a lot in common, and share little with moral thinkers in either the environmental or conservation movement.

I believe that the Wild Equity Institute’s mission helps demonstrate why this is so. The organization believes that the shared moral foundation in our movements is equity: the creation of a more just and fair world. The equitable concerns are easily seen in the environmental justice movement’s focus on the unjust distribution of environmental hazards—and increasingly, also on the inequitable access provided to environmental goods like open space and parks. Similarly, the grassroots conservation movement works to remedy an unjust relationship between human communities and the nonhuman world. As we consume a greater and greater share of the world’s finite resources, less remains for the plants and animals around us, driving thousands of species to the brink of extinction.

While the moral consideration we owe to each other may be different in kind and scope to what we owe to other forms of life, in both cases the gap between what our moral foundation suggests we should do and how we actually act leaves us with a socially balkanized and biologically impoverished world.

The Wild Equity Institute’s purpose is to unite these movements into one powerful force that creates a healthy and sustainable global community for all. We accomplish this by working on projects that highlight and redress the inequitable relationships across our human communities while improving our relationship to the lands in which we live. In that sense, those who focus on equity-–inter-species equity on the one hand, and intra-species equity on the other-–are really part of single movement, regardless of whether their day-to-day work is focused on NOx emissions or invasive plants (and even those are interlinked, science now tells us).

Similarly, Dave Forman, who is one of country’s greatest ethical conservationists, has more in common with the late Luke Cole—an attorney who founded the Center on Race, Poverty, & the Environment, wrote seminal papers on integrating environmental lawyering with grassroots organizing, and was also one of California’s most accomplished birders—than he does with Kareiva, as should be abundantly clear by now. The perspectives of Dave Forman and Peter Kareiva cannot be reconciled into one movement–-even though both ostensibly are attempting “to conserve” wildlife. But Dave’s and Luke’s views could be reconciled into one movement—even though Forman focuses on wildlife and Cole on human-life—because at base they have the same moral foundation—the same fire to put an end to injustice.

The dichotomy between “wildlife-people” and “people-people” is detrimental both because it prevents us from engaging allies and building power and because it adds the illusion of conflict to an area of deeply congruent forms of engagement. We desperately need clarity on this point, because if we don’t know why we stand together, when we face difficult challenges we will likely be confused, respond slowly (if at all), and with disparate tactics. By focusing on our shared moral imperative, rather than the subjects (human or nonhuman) upon which it is focused, the Wild Equity Institute believes we can avoid this outcome. Because it is in our passion for justice where our commonality can be demonstrated most clearly, and from there we can build a more powerful movement for people and for the plants and animals that accompany us on Earth.

[1] Lalasz, R., Kareiva, P., Marvier, M. Conservation in the Anthropocene. Breakthrough Journal, Winter 2012.

[2] Timothy Egan, Fund Raisers Tap Anti- Environmentalism, New York Times, pg 2, December 19, 1991.

[3] Lalasz, R., Kareiva, P., Marvier, M. Conservation in the Anthropocene. Breakthrough Journal, Winter 2012.

[4] Lalasz, R., Kareiva, P., Marvier, M. Conservation in the Anthropocene. Breakthrough Journal, Winter 2012.

[5] Lalasz, R., Kareiva, P., Marvier, M. Conservation in the Anthropocene. Breakthrough Journal, Winter 2012. “Instead of pursuing the protection of biodiversity for biodiversity’s sake, a new conservation should seek to enhance those natural systems that benefit the widest number of people, especially the poor.”

[6] Lalasz, R., Kareiva, P., Marvier, M. Conservation in the Anthropocene. Breakthrough Journal, Winter 2012. “Protecting biodiversity for its own sake has not worked.”

[7] Lalasz, R., Kareiva, P., Marvier, M. Conservation in the Anthropocene. Breakthrough Journal, Winter 2012. “If there is no wilderness, if nature is resilient rather than fragile, and if people are actually part of nature and not the original sinners who caused our banishment from Eden, what should be the new vision for conservation? It would start by appreciating the strength and resilience of nature while also recognizing the many ways in which we depend upon it. Conservation should seek to support and inform the right kind of development — development by design, done with the importance of nature to thriving economies foremost in mind. And it will utilize the right kinds of technology to enhance the health and well-being of both human and nonhuman natures. Instead of scolding capitalism, conservationists should partner with corporations in a science-based effort to integrate the value of nature’s benefits into their operations and cultures. Instead of pursuing the protection of biodiversity for biodiversity’s sake, a new conservation should seek to enhance those natural systems that benefit the widest number of people, especially the poor. Instead of trying to restore remote iconic landscapes to pre-European conditions, conservation will measure its achievement in large part by its relevance to people, including city dwellers. Nature could be a garden — not a carefully manicured and rigid one, but a tangle of species and wildness amidst lands used for food production, mineral extraction, and urban life.”

[8] Lalasz, R., Kareiva, P., Marvier, M. Conservation in the Anthropocene. Breakthrough Journal, Winter 2012. “Instead of pursuing the protection of biodiversity for biodiversity’s sake, a new conservation should seek to enhance those natural systems that benefit the widest number of people, especially the poor.”

[9] Nixon, R. Annual Message to the Congress on the State of the Union. Jan. 22, 1970. Available at http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=2921, (“The great question of the seventies is, shall we surrender to our surroundings, or shall we make our peace with nature and begin to make reparations for the damage we have done to our air, to our land, and to our water?”)

[10] Lalasz, R., Kareiva, P., Marvier, M. Conservation in the Anthropocene. Breakthrough Journal, Winter 2012. “For this to happen, conservationists will have to jettison their idealized notions of nature, parks, and wilderness — ideas that have never been supported by good conservation science — and forge a more optimistic, human-friendly vision.”

[11] Lalasz, R., Kareiva, P., Marvier, M. Conservation in the Anthropocene. Breakthrough Journal, Winter 2012. “The trouble for conservation is that the data simply do not support the idea of a fragile nature at risk of collapse.”

[12] http://rewilding.org/rewildit/around-the-campfire-with-uncle-dave-the-myth-of-the-environmental-movement/

[13] What is Conservation Science? Peter Kareiva, Michelle Marvier. BioScience, Vol 62., No. 11.