Wild Equity recently claimed that the GGNRA’s proposed rule for dog management will, if some modest but essential changes are made to the proposal, create a more equitable park experience for all.

But calling something ‘equitable’ begs the question: equitable for whom?

I’ve been involved with dog management issues for over a decade now, as a dog owner and as a conservationist. I’ve spent an inordinate amount of time considering this question. To a great degree the answer to it is fundamental to Wild Equity’s mission.

When Wild Equity asks if a proposal is equitable, we consider our obligations to each other as well as our obligations to other things. The obligations we owe to other things are nearly always less than what we owe each other, but when we fail to live up to those small obligations there is still an equity gap, and like all inequities we are obligated to rectify it.

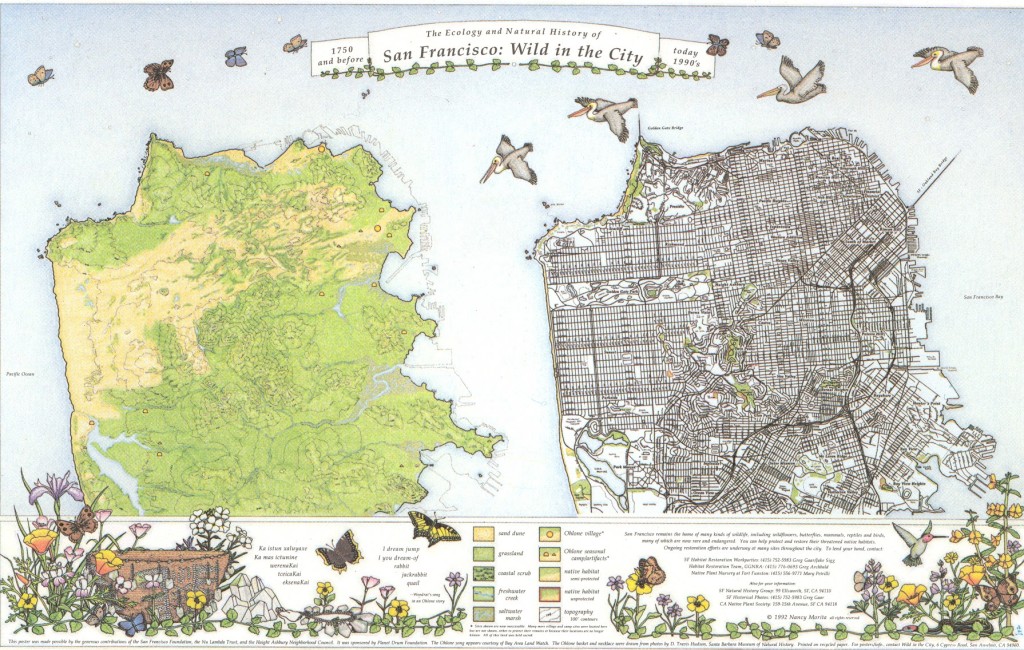

We also consider historical context, in addition to current and future expectations. In San Francisco, where we’ve already transformed nearly all of the land to suit our own desires, the wild flora and fauna have a much more compelling need for the City’s relict lands. This is particularly true when compared to the needs of our dogs, because a significant portion of the land we’ve transformed is dedicated to off-leash exercise: San Francisco has more off-leash play areas per square mile than any other large city in the nation, even before you count the off-leash areas proposed by the GGNRA in its dog management rule.

And whatever you may think about the severity and frequency of off-leash dogs harming others (not to mention themselves), almost every instance of harm is preventable by very simple means: ensuring off-leash areas are safe by fully enclosing them with a physical barrier, and leashing our dogs whenever they are outside these locations.

Yet these simple, common-sense ideas are lacking in the GGNRA’s current plan: physical barriers are not currently required at the proposed off-leash areas, and the GGNRA’s leash law enforcement plan, already riddled with prerequisites and punts, will be impractical to enforce without the clear delineation enclosures provide.

Enclosures also ensure that each visitor gets to choose whether to have an off-leash experience or not, rather than have it imposed upon them simply because they decide to visit the GGNRA. This is particularly important for people with guide dogs (for reasons that are not clear, guide dogs are disproportionately interfered with and attacked by off-leash dogs) and for people who have traditionally been underrepresented in the National Park System. The GGNRA was created in part to remedy that disparity, yet underrepresented groups consistently explain that off-leash dogs limit their access to the GGNRA.

I have been a dog owner all my adult life. My current dog is a maltese mix we adopted from Muttville. He has one good eye, he’s allergic to just about everything, and has a collapsing trachea. But he is a spry gent nonetheless, and he loves to run and fetch. I love him unconditionally.

My perspective as a dog owner adds to my sense that the just thing to do at the GGNRA is to take the park service’s proposal and improve it by ensuring that each and every off-leash play area is fully enclosed by some kind of physical barrier. Doing so will put basic safeguards in place so our dogs don’t become another number in the dataset of hundreds that have been lost, injured, or killed at the GGNRA’s unsafe off-leash areas, while continuing to provide off-leash access in virtually every part of the park where it was historically practiced.

Those accustomed to the laissez-faire dog policy of years past have suggested that they are being unfairly singled out at the GGNRA. And if we didn’t consider the context we are in–more and more of the species found in the GGNRA in danger of extinction, and a larger and larger total population, both human and dog, that wants access to the park–they would have a more compelling equitable claim.

But given all this, the imposition on those who desire status quo access to the GGNRA is more than outweighed by the benefits that will be gained by people, our pets, and the wild flora and fauna of the GGNRA. That’s why we believe the GGNRA’s proposal, with some modest changes, will create a more equitable park for all.